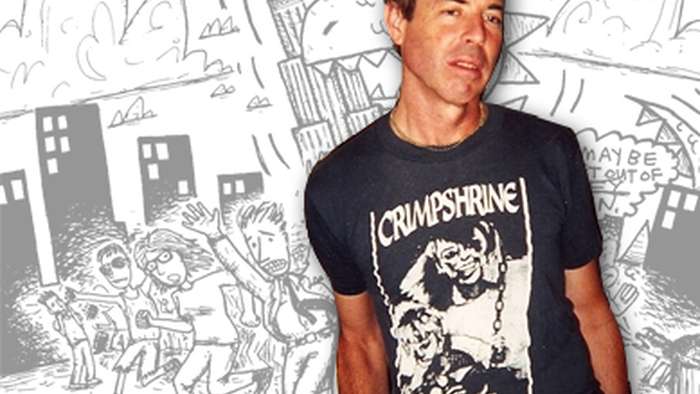

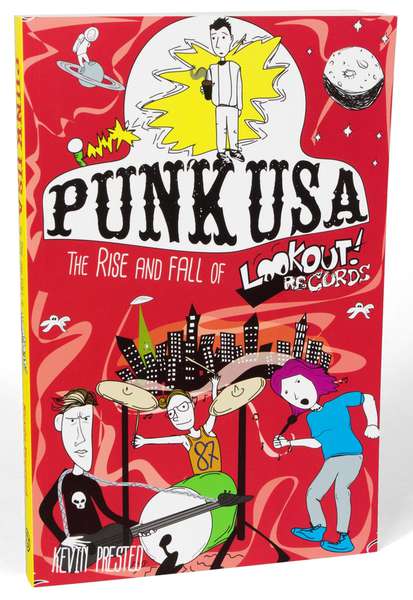

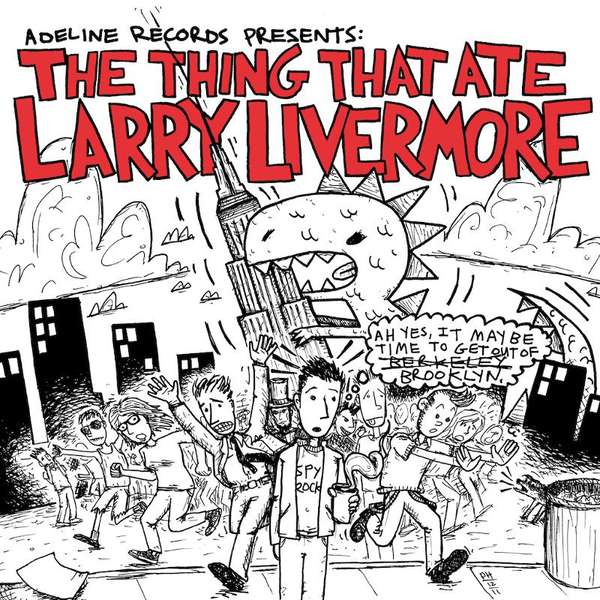

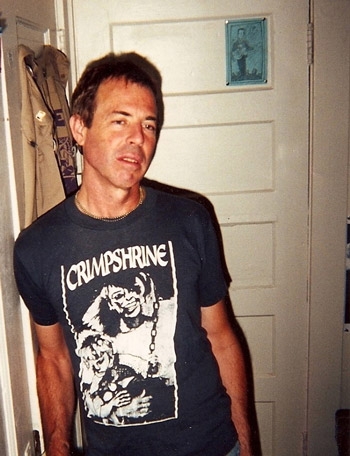

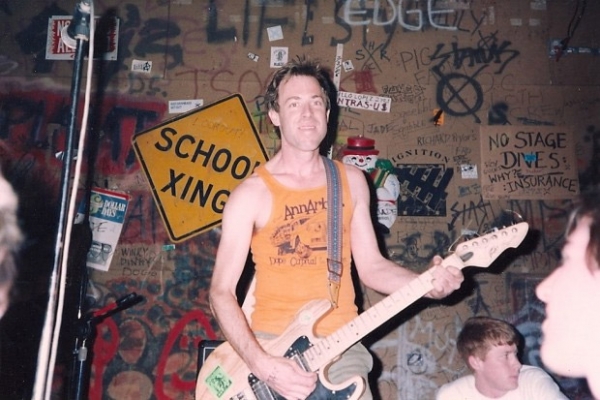

The phrase "elder statesman" doesn't really feel appropriate for the punk scene, but people like Larry Livermore are the closest thing we have to it -- founder of Lookout Records, frontman, columnist, blogger, and now, curator. Larry is teaming up with Adeline Records to release The Thing That Ate Larry Livermore: a compilation of up-and-coming bands that Larry feels need more public exposure, in the same way Lookout used to do a decade or more ago. SPB chatted over email with Larry about the past and future of the punk scene, rioting, novels, and quite a bit more.

Scene Point Blank: When introducing the concept for "The Thing That Ate Larry Livermore", you talk about introducing music to people who might not otherwise hear it, like you did with Lookout in the 80s and 90s. What do you think are the major differences between then and now in terms of releasing a record and promoting a band? Do you think those changes are for the best?

Larry Livermore: The changes are what they are. Each generation has to work with what’s available. The explosion of DIY culture that Lookout was part of in the 80s and 90s was at least in part due to changes in technology that allowed us to accomplish things indie labels and bands couldn’t have done, or at least would have struggled to do a few years earlier. With time it’s become easier and easier to make a brilliant-sounding recording. I hear stuff today that people did on laptops in their bedrooms that’s of higher quality—at least production-wise—than the most expensive record we were ever able to make at Lookout “back in the day.” But no matter how good or not-good your music is, the trick then, as now, is letting people know about it and getting them to listen to it.

Scene Point Blank: Billie Joe Armstrong's son's band features on the record. Did that feel like a conflict of interest or was it simply a case of them being the right fit for the project?

Larry Livermore: I guess you could see it as a “conflict of interest” if there had been any pressure from Billie or the label to put them on the compilation, but actually it was just the opposite. I knew from the start that Emily’s Army was one of the bands I’d want to ask to be on it. So one of the first things I did was ask Billie if he’d be all right with that, to make sure he didn’t see any conflict of interest. Fortunately, he didn’t. Emily’s Army are a great band, the kind of band who love writing and playing music, and who will do well regardless of who any of them are or aren’t related to.

Scene Point Blank: You also talked about your initial desire for people to "take [you] out and shoot [you]" if you got back into the music business. What prompted that feeling, for someone who's been heavily involved with it for decades?

Larry Livermore: That might have been a little hyperbolic on my part, but it’s essentially what I’d been telling interviewers for years when they asked if I’d consider starting a new record label. When I left Lookout in 1997, I was burnt out by the behind-the-scenes machinations of the music business, and disillusioned by having been unable, despite my initial ideals and intentions, to keep Lookout from getting involved in some of the shenanigans and hype that big labels typically engaged in.

At the time I blamed my problems on the industry itself, probably as way of avoiding taking responsibility for my own mistakes and shortcomings. In the first couple years after leaving Lookout, I could barely stand to listen to music at all, especially music that I’d worked on personally, but gradually the hurt feelings faded away and I started enjoying music as much as ever. More so, actually, because I could do so simply as a fan, rather than someone who was constantly being pressured and expected to think of music as some sort of product.

I could have happily gone on that way for the rest of my life, but as I say in the liner notes to the compilation, there came a time when I realized I had an opportunity to do something to help out a bunch of bands I loved by putting them in touch with a bunch of fans who I knew would love them. Which is pretty much the situation I was in when I made the fateful decision to start Lookout: “Well, somebody’s gotta do this. I guess maybe it’s me.”

Scene Point Blank: What's the current status of Spy Rock Memories and when can we expect to see it in print? How has the process of writing it been?

Larry Livermore: The current status of Spy Rock Memories is that it’s taking a hell of a lot longer to finish the final pre-publication work than I ever imagined. It’s frustrating, seeing it so close to done, but not quite there yet. We’ve even got the cover art, an absolutely beautiful painting by the award-winning cartoonist Gabrielle Bell, who also grew up on Spy Rock. The process of writing the book was surprisingly easy and enjoyable; what’s been a bit hellish is editing it. Right now we (myself and my editor, Zach Gajewski) are going through the text for the second time, and I keep finding more things that need polishing up or rewriting. I was hoping the book would come out at the same time as the compilation, but at the rate things are going, I think maybe toward the end of the summer is the soonest we can expect to see it in stores.

Scene Point Blank: You're a pretty prolific blogger and a frequent Twitter user. Are you grateful for not having the internet's distracting presence during Lookout's glory days or do you think it would have improved things?

Scene Point Blank: You're a pretty prolific blogger and a frequent Twitter user. Are you grateful for not having the internet's distracting presence during Lookout's glory days or do you think it would have improved things?

Larry Livermore: Actually, Lookout was an early adopter when it came to internet technology. Depending on when you consider the “glory days” to be (some would argue 1987-89, others insist on 1994-95, and I personally would go for maybe 1991-93), we already had a presence on the worldwide web (does anybody still call it that?) for at least some of those years. And though the early 90s internet contained only a tiny fraction of what’s available today, having to access it through ridiculously slow dial-up modems made it possible to waste just as much time. When we moved into our first “real” offices (as opposed to my bedroom) in 1995 we had the whole place wired for broadband, and I soon became aware that at any given time, half or more of our employees, myself included, were doing something online. On one level, sure, it was a distraction from the important “work” that had to get done, but on another level—the level you could argue virtually every media enterprise operates on today—it enabled us to connect with and keep in touch with people and potential fans all over the world. In the same way that cheap xeroxing made fanzines and punk rock flyers not just possible but inevitable in the 80s, the internet gave us the ability to instantly reach huge numbers of people that otherwise might have never known we existed.

Also, I wish I were a prolific blogger! When I started that thing, it was my intention to post on a daily or near-daily basis. Now sometimes I don’t go near it for a month, despite having (as anyone who routinely sees me in real life will tell you) no shortage of things to say.

Scene Point Blank: Lookout went bust, Punk Planet died, CBGBs closed down. Is the modern punk scene doomed to simply pay homage to what went before or is there new blood and new ideas still to come?

Larry Livermore: Although Lookout only officially closed down this year, I think you could argue that it had been effectively dead for many years, and you could say the same about CBGB. Seriously, when was the last time CBGB was a major factor in introducing new bands or scenes? Like 25 years ago? Punk Planet’s only been gone for five years, but though it was a vital source of ideas and information right up until it shut its doors, it had its roots firmly planted in the 90s, don’t you think?

My point being that what’s happening with punk rock during the first decade or so of the 21st century isn’t just a rehash or revisiting of what went before. I mean, we heard the same thing from scene veterans in the late 80s when the Gilman bands were starting to emerge: “Hey, c’mon guys, don’t you know punk’s been dead since the Sex Pistols broke up? You’re just recycling the Clash and the Ramones.” It used to annoy the hell out of me back then, because I’d been around during the ’77 punk scene, and I knew damn well that what was coming out of Gilman, while influenced by the punk rock of bygone days, was a whole new thing.

As far as I’m concerned, the same is true today. Some of the musicians on The Thing That Ate Larry Livermore weren’t even born when Operation Ivy broke up or when Green Day made their first record. They love that kind of music, but it’s like ancient history to them. Personally, I think punk rock today is more diverse and creative and full of potential than it ever was. Will it ever be as commercially successful as the punk rock of the mid-90s? Maybe not, though you never know. But precisely because there’s no expectation of fame and fortune, precisely because today’s punk rock bands are playing out of pure love for the music and the community that has grown up around it, I find things more fun and exciting than ever. That being said, I can all but guarantee that at least some of the bands on this compilation will be the names people will be talking about 20 years from now when they’re complaining about the bands of 2032 not having the same spark and magic as back in the good old days of 2012.

Scene Point Blank: I know you formerly lived in London and as a Londoner myself I'm curious to know if you have any thoughts on last summer's London Riots. Do you think there are any parallels between the anger those kids felt as they looted shops and the anger of the 80s punks in the Thatcher and Reagan administrations? Or is it simply "mindless violence" like the Conservatives put it...

Larry Livermore: I did have thoughts and feelings about the riots, fairly strong ones. I only lived in London from 1997 to 2007, but I was regularly spending time there as far back as the mid-70s. During those years I witnessed a fair bit of chaos in the streets, but this seemed to be on a whole new level. Except for a brief period in Brixton back in the 70s, I always lived in Notting Hill, and I saw it change from a hippie and West Indian slum into one of the wealthier neighborhoods in London, which in turn gave me a bird’s eye view of some of the tensions and hostilities that were at work last summer. There were minor outbreaks of looting in the Portobello Road, though they were a pale shadow of what happened in 1958 and again in 1976 (the latter, of course, being the inspiration for the Clash song, “White Riot.”

Inasmuch as the events of 2011 could be compared to what went before, I’d say they had more in common with the 1976 Notting Hill riots or the Brixton and Tottenham riots of the 80s than they did with anything specifically punk-related. In each of those there was a racial and a class component, and while punks and young people of all races joined in, the prime movers were black and, to a lesser exent, Asian youth. While I wouldn’t dismiss the violence as “mindless” (in many cases both the looting and the battles with police were remarkably well organized), I also wouldn’t characterize it as being political, at least not in the sense that the anarchist and leftist punks of the 80s were.

During my years in Notting Hill, I lived on a council estate (public housing, as Americans would call it) that had been partially privatized. There many young people, mostly black, Asian or mixed race in our building, and I got to know some of them fairly well, not always under the best circumstances. There was a gang who regularly vandalized the corridors and harassed residents and I took it upon myself to sort out or at least minimize these problems. Some of the kids turned out to be quite decent, but I don’t doubt at least a few of them were kicking in windows in the Portobello Road last summer. Not necessarily out of poverty—they weren’t rich, but neither did they lack for most necessities—and not out of frustration with the direction England was being taken in by the Conservatives—many of them couldn’t have told you the Prime Minister’s name, let alone what party he belonged to—but simply because they were so alienated and isolated from the possibilities and promises that the more privileged and fortunate among us take for granted. When the Sex Pistols sang about “No Future,” it was mostly marketing and hype; for these kids, it’s everyday reality.

Scene Point Blank: Aside from the bands on the Adeline comp, what other artists/records are currently in rotation on your stereo?

Larry Livermore: I’ve long been a big fan of the Weakerthans, and their singer, John K. Samson, has just put out a wonderful solo record. Jesse Michaels, who sang for Operation Ivy, has a new-ish band called Classics Of Love, and their new album is, in my opinion, the best thing he’s done since Operation Ivy. If not for some crossed wires, they definitely would have been on the compilation, too. Speaking of Op Ivy, I recently found a tape copy of the long-lost and never-released Downfall album (the one that Lookout kept announcing and then having to postpone because the band never gave final approval), and I’ve been enjoying that all over again. One of my favorite local bands here in New York, though they’ve been broken up for a couple years, was the Steinways (their singer/guitarist is now in House Boat). Delay are an outstanding band from Ohio, and I recently rediscovered For Science, from New Jersey (also broken up), who I sadly never got into when they were around, but who I really appreciate now. Plus I’ll always enjoy my hillbilly music, my Broadway show tunes, and my doo-wop, soul, and rock and roll oldies.

Scene Point Blank: You've blogged in the past about online spaces like the Pop Punk Message Board, and how they've come to represent the best parts of the 'old' punk scene. With print magazines in seemingly terminal decline do you think these types of places are good for the wider punk community?

Larry Livermore: I’d hesitate to venture an opinion as to whether they’re “good” or “bad,” they’re just what is. As always with alternative culture, with any kind of culture, really, we do what we can with what we have. People romanticize all sorts of things, be it vinyl records, cassette tapes, xeroxed flyers, hand-lettered fanzines, crappy cheap-sounding recordings, whatever, as representing the “real” punk aesthetic, but punk just happened to come in those particular packages because that’s what was available for people to work with at the time. It doesn’t make something less “punk” or “authentic” to use the technology and media of today; if you didn’t, it’d be like trying to work with one hand – if not both – tied behind your back. I don’t mean that as a dig against those who cherish those old school approaches to communication and community. But in my view, social media, message boards, online hangouts, etc., are just that many more tools to accomplish what we’ve always tried to accomplish: creating awesome art, music and culture and making it available to those who want and need it.

Scene Point Blank: Finally, what's next for you? Once the book and this comp are out, do you see yourself swearing off music once more, or could you be persuaded into something else?

Larry Livermore: Writing is probably going to be the main thing I do for the foreseeable future, that and traveling. I’ve got two more books on the agenda after Spy Rock Memories. But considering what a good time I’ve had putting the compilation together, yeah, I think I could see doing a little bit more work with music. Maybe helping a few bands I like get signed, maybe some production work, maybe a little talent scouting. Who knows? I’m open to it, but probably not as a fulltime job. As long as it’s fun and I feel like I’m accomplishing something worthwhile, why not?