The number one criticism that I hear about Foxfires is that there are too many words in the songs.

I’ll level with you. The real number one criticism is that once the Jameson is gone, the inside jokes about the forced milk-drinking meme have gotten old and it’s time for bed. That one doesn’t bother me. The one that stirs emotion is the one about the lyrics.

The criticism is valid. What kind of dipshit kicks off their record with a 45-second song that has 95 words in it? According to my Construction Master 5 calculator, that’s 2.111 words per second. The math has now moved beyond my capability, but that’s indicative of Marginalia and, frankly, our entire catalog.

Lyrics are important to me. I don’t mean to imply that I’m good at writing them. If I’m being honest, I’d probably describe my relationship with lyric-writing as a semi-constant freakout. Melodies, rhyme schemes, those things are awesome, but for me, the point is always the story.

Something I have to get out of the way right now: it is impossible to talk about song lyrics and not sound like a complete asshole. I’m not an asshole, really, but I do take writing pretty seriously and I’ll understand if that’s the impression you leave with. I owe you one Genesee Cream at Ralph’s Diner when things get there.

I grew up idolizing Hot Water Music. While the majority of what I listened to as a wee freckled Massachusetts lad was hardcore, I really attached myself to this particular post-hardcore act. They were bleak at times, but there was always a light shining through. That was something I needed to hear as a kid, apparently.

It made me introspective. Fuel for the Hate Game and Forever and Counting in particular really hit me. I’d stay up in my room all night, reading along to every song. I stared at Scott Sinclair’s album art in amazement. Perhaps embarrassingly in retrospect, I even had lyrics from "Us and Chuck" as my high school yearbook quote.

The embarrassing part isn’t the lyrics, it’s that I had a grown-out ginger bowl cut.

All of that is to say that those years of obsessively reading and listening to their lyrics had a profound impact on me. I couldn’t always understand them right away, but I wanted to. I wanted to listen to this ugly, beautiful story someone I had never met was telling me that made me smile, made me cry, made me angry and made me motivated all at the same time. For the first time in my life, I really cared about what a band had to say.

Around the same time a friend gave me a tape with Boston’s The Suicide File on it. There were tons of other bands on there that were also important to me, but Dave Weinberg’s vocals and lyrics spoke to me. I couldn’t believe how fucking angry he sounded. At the time, I was going to hardcore shows every weekend and I was plenty familiar with angry, but it was obvious that The Suicide File wasn’t writing angry music for anger’s sake. They had something to say. I could write an entire story on their output, but to avoid Loren’s ire, I’ll just say this: it is incredible to me that they recorded “Ashcroft” over 15 years ago and it might be more relevant today. They were a perfect example of a band that all but required you to care about the message.

Later, Dominic Mallary altered the way I thought about lyrics forever. Dom was in a number of fantastic bands, but Last Lights, in my mind, was the most powerful force to ever come out of Central Massachusetts and Dom was an absolutely brilliant writer. I was lucky to call him a friend and while his sudden and tragic death was and still is devastating to everyone that had a relationship with him, I often reflect on the words he left with us.

His lyrics were hugely important to many people, myself included, but it was a non-lyric quote of his that floats around in my head most often: “Hardcore without punk isn't music, it's a genre of porn. And punk isn't a genre of music, it’s a thought process.”

I’ve thought about it a lot over the years. It changed the weight I attached to lyrics significantly. Why am I writing “angry” music? Is the music angry for the sake of anger? Is it a spectacle, or is there reason behind it? What am I saying and what will someone listening take from those words?

Why am I writing “angry” music? Is the music angry for the sake of anger? Is it a spectacle, or is there reason behind it? What am I saying and what will someone listening take from those words?

I was lucky enough to tour the world during my time in Four Year Strong and meet numerous talented musicians along the way. I learned some really interesting tidbits about different styles of writing. Some things I held onto. Internal rhyme, for example. A really fun and interesting way to write when you feel so inclined and a very effective tool for someone who needs to stuff a few more syllables into a short song.

Some, I didn’t care for. A common theme I heard was to change words to make songs more relatable. For example: “We want pizza!” rather than “I want pizza!” (I hope those of you who survived pop-punk can appreciate the reference) I understand the purpose, but I’ll use the royal we when necessary and I’ll talk about myself as a narrator if that’s what is needed. I’m writing the songs here, not a marketing team. How can these things be interchangeable unless I don’t know what I’m trying to say?

I’m not stupid. I understand that to achieve a certain level of success, you may have to tailor your songs for a wider audience. If you’ve ever listened to Foxfires, you probably knew within 30 seconds whether or not we were your cup of tea.

There’s quite a bit of power in that.

Not buy an all wheel drive vehicle with less than 100,000 miles on it power. Not fancy exposed-brick facade loft apartment-renting power. But power in being able to write whatever music we want. Nothing is tailored for anyone except for myself and the people that trust my words alongside their music. That’s powerful.

NOTE: If you’ve made it this far, I appreciate you and I’d appreciate it even more if you’d send me a sample joint of the weed you’re smoking. In a roundabout way, I’m nearly positive I will be arriving at a point here shortly.

I listen to music for how it makes me feel. While I can occasionally enjoy music on its own merits, most of the time I am uniquely cursed in having to connect with the lyrics of a song in order to really appreciate it. The harshest thing anyone could say to me, or that I could say to anyone else, is that their words have no meaning.

You see it in every genre. I could cast stones in the direction of modern pop, but hardcore can be just as guilty. I also want to be clear: I’m not saying music with lyrics I can’t connect to aren’t good. If any song makes you feel the way you want to feel, fucking listen to it. Keep in mind, I’m just a chowderhead drinking instant coffee in Worcester, MA and I don’t know any more or less than anybody else.

Pre-pandemic, my career as a journalist came to a screeching halt. Anyone vaguely familiar with the news these days already knows the story of the imperilled publication. Plucky independently-owned alt weekly gets bought out by vulture capitalists, everybody gets fired, the thing gets gutted. Then the pandemic hit and I’ve had to make some pretty massive adjustments in my life. Not for the first time, it wasn’t that long ago I could say I made my living as a professional musician, or a truck driver, or a package handler at a shipping company.

Anyway, a frequent criticism in my feature stories (and my entertainment column, but I leaned into that one) from my editor was that I needed to tighten shit up a little bit. Economy of words can be important, sure, but I didn’t enter journalism through journalism school. I stumbled through the back door after writing short fiction and -- apparently -- finding the right magazine that was the right kind of desperate. It occurred to me where this all came from while I was being relentlessly taunted by high school students at a career-day presentation.

Let me set the stage.

I was well into my 30s. Self-conscious, naturally, and lacking much of the confidence I had acquired through my younger, wilder, more consequential years. Most of the students used this time as a way to take a nap, which I understood and would have taken advantage of myself back at Wachusett Regional. One student immediately asked how I became interested in writing. I was hungover and nervous, sweaty and out of my element (I see a lot more dogs than I do children) and I answered truthfully and with the first thing that came to my mind: I fucking loved The Hobbit.

Now I have to pause briefly because this answer would prove to be somewhat consequential to the bloated chunk of meandering hubris before you. I never got a chance to expand on that thought, as two other students who were apparently aware of my time in Four Year Strong (the teacher, who is a close friend politely asked them to mention Foxfires as well. Thoughtful, yes, but I know the deal) changed the subject.

“Do you ever miss it?”

That one kicked my ass. It was the final question I would get, too. I floundered pretty savagely and then was mercifully sent back to my Nissan Sentra that left the lot the same year I graduated from high school and returned home.

Regardless, The Hobbit and Tolkien’s work in general shaped my interest in writing. If you’re wondering where the tie-in for all this is, I’ll do my best.

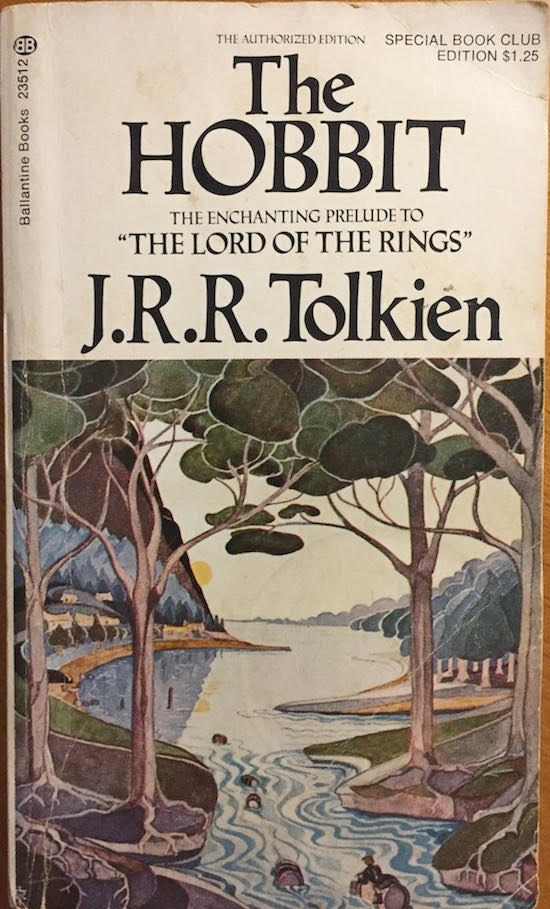

I was introduced at a very young age to The Hobbit. My father gave me the copy he read when he was young himself, a 1973 paperback with a whimsical watercolor and ink painting of The Shire on the front and a smiling, smoking Tolkien on the back. I still have it. It’s in tatters, but I still read it every few years and I’ll keep it until it crumbles into dust, or I do.

I was young enough at that point where I had a pretty limited vocabulary. At the time, I was living in rural Vermont and New Hampshire and had plenty of time to read. But, moreover, I had plenty of time to understand.

I didn’t know a lot of the words in The Hobbit the first time I read it. I sat there with a massive dictionary my blood-grandfather left my mother and used it as a cipher while I worked my way through. I loved the process. I didn’t just understand this little world of hobbits and dwarves and men and dragons and wizards, I was beginning to understand my own language better. I took it as a challenge then and I take it as a challenge now.

I want to understand the words a writer puts to paper. I give them complete trust that they finely-tuned and cared for each syllable. I want to understand what the writer is telling me, I want to be there for their journey. Not everyone wants to appreciate music like that and I get it. Frankly, between my own mental issues and my experience in the music industry, it’s a miracle I can appreciate music at all.

For those that understand where I’m coming from, for those that read along and wonder what the writer of the book, or the poem, or the song meant and devote a bit of thought to both that and your relationship to those thoughts, I think you might find something to enjoy in our little band. It’s OK if you don’t, really. We aren’t designed for mass consumption and we’ve played enough Tuesday-evening basement shows to know exactly where we fit into this big ‘ol noisy world.

I’m not going to write about what my lyrics mean -- and not because I think that songs can mean anything the listener wants them to. They can mean all sorts of things to the listener, of course, but for me, the songs mean something very specific, very real and I worked quite hard on them. I think some fellow lost soul out there might find our distant-but-shared experience cathartic. It just may take a few listens to get there.

For the handful of you that found any of this intriguing I’ll say this, if you’ve ever seen an Oxford comma on one of our lyric sheets, or the word grey spelled “gray, ” just know, somebody else added it in.

Cheers.